Teacher question:

I teach kindergarten. Our school recently purchased the XXXX program for teaching decoding. I don’t like it as much as the program we had. One of the ways our previous program was better than XXXX is that it included pictures for each of the phonemes. The new program does not have those pictures and I think that is a real problem. Is there any evidence that I’m right that I could take to my principal? The other teachers agree with me.

Shanahan response:

I hate that question and I wish you hadn’t asked it.

Oh, sure it’s a practical question. And as a former first-grade teacher I get why you’d ask.

But it points out an error I have made in the past.

When I used to prepare primary grade teachers that question came up sometimes. And, I answered it… incorrectly.

I answered it on the basis of logic, a dangerous approach.

“Professor Shanahan is it a good idea to use pictures when you are teaching letter sounds?”

“No, impressionable young preservice teacher. It is a bad idea. Children have to learn the letters and the sounds. Adding a picture to that equation means that there is just one more thing the kids have to memorize. It is hard enough to memorize 52 letters, and 44 sounds, without having to memorize 44 pictures to go with those sounds.”

I love that answer. It makes so much logical sense. I sure sounded wise to those young women (and the occasional guy).

And, yet, I was wrong.

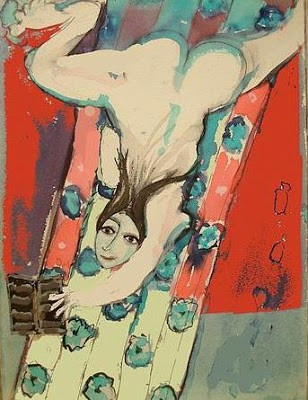

The research these days shows just the opposite. Using what are referred to as “embedded mnemonics,” that is pictures that remind the children of the letter sound, actually improve learning. Across various studies (Ehri, 2014; Ehri, Deffner, & Wilce, 1984; McNamara, 2012; Schmidman & Ehri, 2010) it has been found that such embedded mnemonic pictures can reduce the amount of repetition needed for kids to learn the letters and sounds, with less confusion, better long-term memory, and greater ability to transfer or apply this knowledge in reading and spelling.

Art Credit: The example of a visual mnemonic for teaching decoding was provided by the artist Cat MacInnes, from www.spelfabet.com.au/materials”

If one relies on data – rather than reasoning – the answer is kind of a no-brainer — it is a good idea to use embedded mnemonics. It looks like, at least with regard to this feature, your previous program was better than the new one.

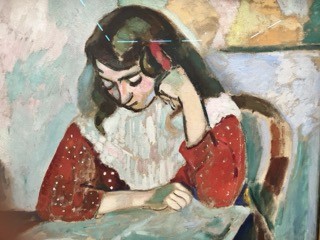

But let’s be careful with this. What’s good in this case (the use of pictures) is not such a great idea when you are teaching words. Research has long shown that when teaching words kids do better with just the letters without any pictures.

Why would that be?

The pictures have been found to distract from the information that you need to remember a word. In that case, students don’t need a visual mnemonic -- they need to focus their attention on the combination of letters. That’s what you want them to look at. If they spend time examining the picture instead of the letters, they are less likely to learn the word.

With something as specific or one-dimensional as a letter or a phoneme, an embedded picture provides a useful mnemonic (memory support), neither distracting students from what needs to be learned or overwhelming memory. With more complex or multidimensional items it is better to focus student attention on analyzing the parts. That’s why, when I’m teaching kids to read some high frequency words, I have them look at all the letters and spell the word and try to write it from memory.

But when it comes to teaching letters and sounds, no question about it, use embedded mnemonics. They work.

And, as for answering questions about what works in reading? An instructional approach is not "best practice" just because it makes sense. That's why we use research. A lot of times, those things that are sensible are, well, not a great idea!

References

Ehri, L.C. (2014) Orthographic Mapping in the Acquisition of Sight Word Reading, Spelling Memory, and Vocabulary Learning, Scientific Studies of Reading, 18:1, 5-21, DOI: 10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

Ehri, L. C., Deffner, N. D., & Wilce, L. S. (1984). Pictorial mnemonics for phonics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(5), 880–893. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.76.5.880

McNamara, G. (2012). The effectiveness of embedded picture mnemonic alphabet cards on letter recognition and letter sound knowledge. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Rowan University.

Shmidman, A., & Ehri, L. (2010) Embedded picture mnemonics to learn letters. Scientific Studies of Reading, 14:2, 159-182, DOI: 10.1080/10888430903117492

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.