Teacher Question:

I’m a second-grade teacher. Our school has purchased a reading comprehension program that emphasizes visualization. Is that such a good idea?

Shanahan Response:

Great question. This is one that I can answer with a “yes” or “no.”

I’m not answering like a politician, it just sounds like it.

My affirmative and negative isn’t an attempt to be on all sides of an issue. It’s just a recognition that visualization has been a successful instructional strategy… at some grade levels; and not so much at others. That means that program might be a good purchase for some of the teachers, but maybe not for you.

Basically, the idea of visualization is to get students to translate the text information into a mental image. Of course, doing that means the readers have to think about the text ideas (and that’s a plus) and if they are successful in seeing the information in their heads that should improve memory for the information (a second plus).

Visualization was also one of the comprehension strategies that was found to improve reading comprehension. The average effect sizes were not as high as for some of the other strategies evaluated but the results were positive and, truth be told, there are strong theoretical reasons to promote visualizing.

Some reading theories (specifically, dual coding and embodied cognition) maintain that visualization – and the forming of other kinds of sensory representations during reading – are an important part of the comprehension process itself. In other words, visualizing doesn’t help comprehension, it is part of the comprehension process.

There is plenty of evidence showing that better readers are better visualizers.

Authors provide linguistic information through their writing. They create texts. Readers, to comprehend those texts, must translate this information into what the researchers refer to as a “situation model.” This situation model is just a mental representation of the text, and it includes both linguistic info from the text and the reader’s own prior knowledge.

There is strong agreement that these mental representations are not linguistic, or more accurately, not linguistic alone, and that situation models include all modalities (visualization includes mental pictures and sounds and smells and tactile information).

It gets really interesting when you look into the neurological studies of all of this.

These studies look at the localities of brain activation while people are reading or listening to brief texts. With older proficient readers (8-11 yrs.), they activation in the occipital regions of the brain suggesting visual or imaginative processing in the right hemisphere. But this kind of activity is not evident with 5-7-year-olds when they are reading. Instead, their brains appear to be more focused on coordinating the visual representations of the words with phonological processing. On the other hand, when listening to narratives, these younger students evidence active processing in the occipito-temporal regions. This neural activity during listening was even predictive of how well these students would read later.

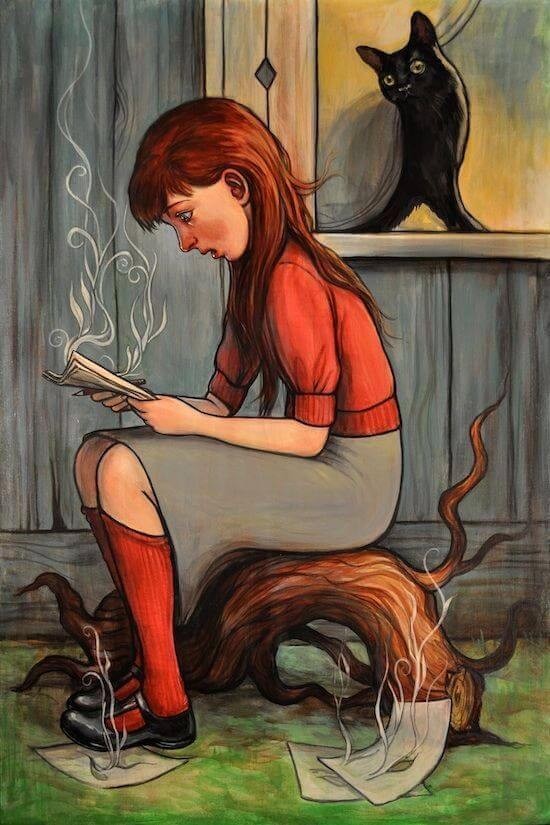

That means that visualization is evident in reading in grades 3-5, but not so much in grades 1 and 2, at least when it came to reading. There appears to be a shifting of neural activation when reading from ages 5 to 11. (Maybe that’s why illustrations are so important to younger children; the text provides the pictures they can’t or won’t create on their own.)

I mentioned that engaging kids in visualization can lead to improvements in their reading comprehension. The teaching studies are consistent with the brain studies. Basically, visualization improved comprehension in the upper grades but not in the primary grades. Hence, my yes and no answer.

Telling kids to “make a picture in your head” has just not been very effective. When it has worked, it has helped the older kids, not the second graders; and the effects have been relatively modest – it works, just not as well as some of the other strategies.

The versions of visualization that have been most effective have confounded it with an even more effective comprehension strategy, use of text structure. For example, kids are taken through a series of visualization steps that engage them in thinking about the text structure: make a picture in your head of the setting, now see if you can close your eyes and see the character, now see character’s problem, and so on.

So, I ask myself what’s working here? Is it the visualization or the structural guidance? Perhaps both are helpful.

In summary, visualization is a part of the comprehension process, and it is part of how most humans represent information in memory. It becomes part of reading once students have developed sufficient automaticity with the visual/phonological aspects of reading. Personally, I wouldn’t do a lot with visualization for reading in those early years; I’d save that training for when they’re a bit older and more accomplished as readers. With the older kids I would try to link their visualizing to structural properties of text (hedging my bets).

References

De Koning, B.B., & van der Schoot, M. (2013). Educational Psychology Review, 25, 261-287.

Horowitz-Kraus, T., Vannest, J.J., & Holland, S.K. (2013). Overlapping neural circuitry for narrative comprehension and proficient reading in children and adolescents. Neuropsychologia, 51, 2651-2662.

Sadoski, M., & Paivio, A. (2001). Imagery and text: A duel coding theory of reading and writing. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Sadoski, M., & Paivio, A. (2004). A duel coding theoretical model of reading. In R.R. Ruddell & N.J. Unrah (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (5th ed., pp. 1329-1362). Newark, DE: International Reading Associaton.

Sadoski, M., & Paivio, A. (2007). Toward a unified theory of reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11, 337-356.

Zwaan, R. A. (1999). Embodied cognition, perceptual symbols, and situation models. Discourse Processes, 28, 81–88.

Zwaan, R. A., & Radvansky, G. A. (1998). Situation models in language comprehension and memory.

Psychological Bulletin, 123, 162–185.

Zwaan, R. A., Langston, M. C., & Graesser, A. C. (1995). The construction of situation models in narrative

comprehension: an event-indexing model. Psychological Science, 6, 292–297.

Zwaan, R. A., Stanfield, R. A., & Yaxley, R. H. (2002). Language comprehenders mentally represent the

shapes of objects. Psychological Science, 13, 168–171.

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.