Blast from the Past: This entry was first published on October 4, 2016 and was reissued on February 29, 2016. The reason for revisiting this one is the steady accumulation of new research data supporting my original contentions. The latest studies are reporting that independent reading can have positive impacts on learning, but that these payoffs take a very long time to manifest and are quite small (Eklund & Torpa, in press). Studies are also showing that reading achievement has a decidedly bigger impact on motivation than the other way around (Hebbecker, Förster, & Souvignier, 2019).

Teacher question:

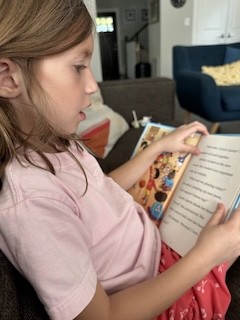

You have attacked DEAR time [Drop Everything and Read] because you say it does little to raise reading achievement. But what about having kids read on their own as a way to motivate them to be readers? As a teacher I want my kids to be lifelong readers, so I provide 20 minutes of daily independent reading time. What do you think?

Shanahan response:

I think you sound like a nice teacher, but perhaps not a particularly effective one.

As you remind me, the effects of DEAR, SSR, SQUIRT or any of the other “independent reading time” schemes are tiny when it comes to reading achievement. Many of those studies have not been particularly well done, but even when they have been the learning payoffs have been tiny.

Surprising to me is that this pattern holds even with summer reading programs — which should be the clearest test of the power of such reading (since recreational reading isn’t replacing other academic activities during a school day). James Kim has studied that kind of thing a lot and while he concludes that some very small learning benefits can be derived from such programs, he has had a lot of difficulty obtaining even those result from study to study.

Unfortunately, the motivational impact of such procedures has been studied less—and with even less payoff. In my experience, the better readers enjoy the free reading time—so they continue to like reading even within a DEAR time framework—but the other kids don't enjoy it much since they don’t read very well. Yikes!

I definitely understand the logic that you are working with—I believed in it as a classroom teacher. The idea that kids practicing independent reading would make them want to be independent readers in the future seemed compelling at the time. But when you think deeply about the practice, its problems become more evident.

How do kids perceive these practices? I know one program that requires kids to read 45 minutes per day on their own at school and another 45 minutes at home. This doesn’t seem particularly “independent” since it is mandated and I’m not sure that kids see this as being qualitatively different than the more circumscribed reading assignments in traditional textbooks. So what is it that distinguishes so-called independent reading from other classroom assignments?

1. Whether the reading is going to be done or not.

If the teacher makes me read for the next half hour, that doesn’t seem particularly “independent.” She might let me choose the text I read, and she doesn’t make herself available to provide assistance, but what if I’d rather not read at all or would prefer reading during math class? Now that would be independent. Required reading time — even when it does not include much teaching — isn’t inherently motivational for everyone (studies show reading motivation to be closely linked to how well kids can read and their home background). Making somebody do something may accomplish compliance, but compliance doesn’t necessarily contribute to motivation. (As they say, you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him take a bath.)

2. Whether the reader picks the text.

This one is a bit easier. In fact, many experts talk about “self-selected” reading rather than independent reading, since book choice may be the only agency students are allowed in these routines. Lots of times the unmotivated kids still can’t find anything they want to read, and, of course, there are complications. Many teachers/schools constrain these “free choices,” such as only allowing students to read books at particular levels (à la Accelerated Reader). If I can choose only books with blue dots, then my choices are decidedly constrained; and if I’m not particularly interested in reading about any topic, then choice wouldn’t be much of a motivator. (Someone I know is fascinated with tennis. I once bought him a book about tennis, sure he’d love it. Instead he was a real pill: “I love playing tennis, not reading about it.” There is an important motivational lesson there.)

3. How accountable is the reading? Do I have to answer the teachers’ questions? Or write a summary to be evaluated? Or read a segment aloud so the teacher can check on my fluency? Or discuss this with the book club group and not look like an idiot?

As research accumulated exposing the lack of learning from unaccountable reading (e.g., DEAR, SSR), teachers started adopting procedures for conferencing with kids about their books. In other words, they are trying to make independent reading more like reading lessons — we’ll determine the levels of the texts that you will be allowed to read and you must prove you read the material and understood it; not exactly how most of us use our free time. My point isn’t that such accountability is bad — au contraire — but certainly doesn’t seem particularly well-aligned with the idea of fostering a love or reading.

See what I mean? The logic of requiring kids to read for enjoyment doesn’t seem as brilliant as it may have at first blush.

What does motivate us? I’ve read a lot of that literature on motivation and being required to do something never comes up as a powerful stimulator of lifelong desire; though self-control does. Being sent off to do something on one’s own has not been found to entice kids (it can feel isolating) but working cooperatively with others has. Being engaged in activities that provide a sense of accomplishment or fulfillment may contributed to a lifelong love of literacy, but how much accomplishment or fulfillment do you think most of the poorer readers get from such “independent reading”?

If you don’t want kids to love reading, then focus on motivation rather than learning. Instead of providing explicit teaching and stimulating group discussions, require that they choose books by F&P levels, read them on their own, and punctuate this supposedly motivational routine occasionally with one-on-one conferencing. (Not surprisingly, the extensive scientific literature on motivation doesn’t entertain such practices as being likely to stimulate motivation).

But if you really want kids to love reading, teach them to read. Achievement does more for motivation than the other way around. Set up opportunities for kids to work together and with you around books. Encourage them to include reading in their daily live away from school. If you want them to care about books, give them a chance to take on books that may be too hard for them, but that they think to be worth the effort. Give them ways to gain social rewards for using the knowledge they gain from their reading.

I appreciate your evident devotion to your students. I hope you care so much that you’ll be willing to alter your methods to meet your very appropriate goals for them.

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.