Teach Your Baby to Read

Awhile back, an entry here focused on the “Teach Your Baby to Read” program. I criticized those programs for fostering a mis-definition of reading as word memorization and said it was not likely to be effective. I pointed out the need for research. That turned out to be a controversial blog and it generated lots of response. Most critics were parents, two of whom even offered to bring their toddlers to me to see that they were reading.

It is hard to invest in something that doesn’t work; it creates “cognitive dissonance.” That’s just a fancy way of saying that people look hard for reasons to like those things that they have already bought into. Buy a new car and you start reading more car ads than before because you look for evidence that confirms your good judgment.

This week, Susan Neuman and her colleagues published, in the Journal of Educational Psychology, a randomized control trial of studies on baby literacy programs. Their conclusion: “Our results indicated that babies did not learn to read.” The programs had no impact on measures of early literacy and language. Nevertheless, the parents who delivered the programs were sure they were working. Cognitive dissonance strikes again.

Teaching Vocabulary to English Learners

My recent blogs on academic vocabulary elicited this request: “I love that you are addressing this topic! Any advice for those of us working with large populations of ELL students?”

It's a good question. Research suggests vocabulary learning supports reading comprehension, and this impact is greater with ELLs than native speakers. ELL students are less likely to know English words, so teaching words would have a particularly powerful impact for them.

One thing that is different for ELL kids is that it is not just academic vocabulary that they lack. If we only teach book language or the words that aren’t usually heard in oral discourse, then ELL kids may be left out. It is essential that ELLs be assessed to determine their language status. If their language development is similar to that of their English classmates, then emphasizing academic vocabulary with them makes great sense.

More likely, however, their language will lag behind. In such cases, providing them with additional instruction in vocabulary would make sense. But this instruction should focus on oral language—not written. Claude Goldenberg has promoted the idea of having a daily period devoted to English language instruction for ELLs and that makes great sense to me. Give these kids a chance to close the gap with their English-speaking peers.

I would also argue that it is important to do more than teach word meanings. That has value, of course, but so do listening comprehension and grammar lessons. Language includes more than words.

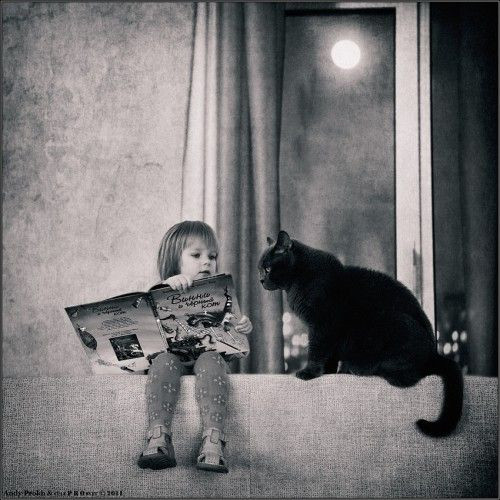

My Daughters

There have been many responses to my blogs about teaching my daughters to read. The most chastening was from my eldest who claims I attributed the anecdotes to the wrong daughters. That may be the case, as since they were little, I often would call them by the wrong names. I always told them they were lucky that we didn’t have a dog (who knows they might have come to think Fido was their name).

I also heard from someone who wanted to know the impact of teaching the girls on their later school performance. E., the oldest, who entered school reading at a third-grade level, was chagrined to find that the kindergarten teacher would spend the year teaching letter names and sounds (she enjoyed the inflatable letter people). They let her attend first-grade part-time that year which didn’t help much since those kids could read either. She loved the freedom of being able to leave kindergarten for first-grade and, to her thinking, it was a good year. She later skipped a grade to try to get a closer match (I wish we hadn’t done that, but it was the only choice given the teaching available to her at the time—not the case in all schools).

M., the youngest who was slow at language learning, entered kindergarten with more modest accomplishments (she was reading at about a grade 1 level). Her advantages were less obvious, but I suspect more valuable. There was a very real chance that M. would have struggled with reading when she entered school. Instead, her biggest weakness was a modest strength. I have long believed that if I hadn’t taught E. to read, she would have learned at school quickly and easily anyway. M., on the other hand, may have languished with the wrong teacher or program, and she may have played catch up in language from then on. Her reading levels might have been less remarkable initially, but her reading success was guaranteed.

Both girls did well in school, and one has a degree in law and the other in engineering.

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.