What Should Morphology Instruction Look Like?

-

academic vocabulary

academic vocabulary  19 August, 2018

19 August, 2018 33 Comments

33 Comments

Teacher question:

Are there any resources that provide a list of morphemes to teach at each K-5 grade level? I have been looking for a definitive list of morphemes that is organized by grade level like the Fry sight word list. I often come across research about how L1 and L2 students acquire morphemes, but I am looking for a list that represents the morphemes that students will most likely see in print at each K-5 grade level. Does anything like that exist? Thank you for your time.

Shanahan response:

The short answer to this question is, “No, I don’t know of such a list.”

But when have I ever been satisfied with the short answer to anything?

Let’s make sure we’re all in agreement as to what constitutes a morpheme? Basically, a morpheme is the “smallest grammatical unit.” It isn’t the same thing as a word, and yet many words are morphemes. The distinction turns on whether the unit (the morpheme or word) can stand on its own. Words have to have that kind of independence, while morphemes don’t require it.

Thus, bags, trucked, running, and redirect are all words in the English language while bag, s, truck, ed, run, ing, re, and direct are all morphemes. Each morphemic unit carries meaning, but sometimes morphemes can do that independently (bag, truck, run, direct), and sometimes they need to be combined with other morphemes to be considered a word (s, ed, ing, re).

I admitted ignorance on this issue, and I’ve tried to turn that ignorance to your advantage. I contacted Jeffrey and Peter Bowers. Both are outstanding scholars (Jeff at the University of Bristol in the UK, and Peter at WordWorks Literacy Centre, in Ontario) who are particularly knowledgeable about teaching morphology to improve literacy. They’ve both published widely on the issue, and both have chided me when they felt I wasn’t paying sufficient attention to how words work morphologically. These days I know no one better able to provide you with a thoughtful answer to your question, and boy was I right! I apologize for the poor renditions of the Word Matrix and the Word Sums. I'll be working with my webmaster to get the real graphics in, but in the meantime you can go to the Word Works website to see them in their full glory. http://www.wordworkskingston.com/WordWorks/Home.html

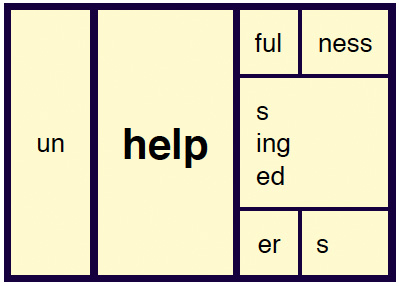

Word Matrix: A map of a word family

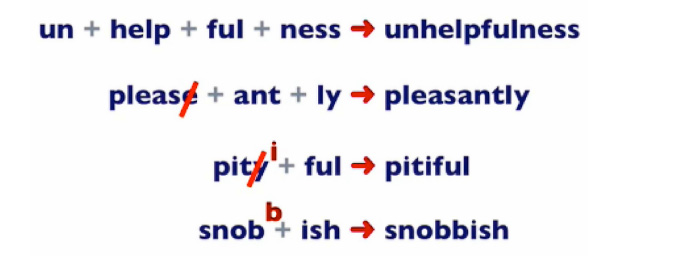

Word Sums: reveal underlying structure of any complex word (a word with more than just a base)

Here is Peter Bower’s response (with my light editing):

“I have no knowledge of such a list, but I wouldn’t recommend one anyway.

“My recommendation based on theory not direct research evidence — is that the main value comes from teaching all or many members of a morphological family at one time with the matrix and word sums (see the attached figure illustrating a matrix and word sum). In the younger grades I start with free bases [those morphemes that stand alone as words], but once that is established, I have no trouble introducing bound bases [the units that can’t stand alone]. This relates to the research we cite about the value of studying meaningfully related items at one time rather than disconnected items.

“Instead of a “scope and sequence” of morphemes to teach, what I recommend is starting with words in the children’s vocabulary, analyzing such words to find their bases, then looking for other members of that family.

“The point is not that there is a “scope and sequence” of morphemes to teach. Rather there is a kind of a “scope” of orthographic concepts that we want students to learn, and teachers can address those concepts based on whatever words are central to the readings they are introducing to the students.

“A brief list of those concepts that should be taught would include:

- Every word is a base or a base with something else (another base or affix)

- Bases and affixes (morphemes) are the meaningful building blocks that construct words.

- We can analyze complex words into constituent morphemes with word sums and show their interrelationship with a matrix.

- English spelling prioritizes consistent spelling of morphemes over consistent pronunciation of morphemes. (This is why we refer to morphemes by their spelling not their pronunciation. The base of the word action is not referred to by the pronunciation of the word act. Instead it is referred to by its spelling. The base “a - c - t”. This is the same as the fact that we don’t refer to the <-ed> suffix by one or all of its three pronunciation, we call it by it’s spelling “e-d suffix.")

- Thus, we need to understand grapheme-phoneme correspondences from within the context of morphological families. (e.g. we learn the phonology of the grapheme by studying morphological families).

- There are reliable conventions for the three suffixing conventions.

- Studying and understanding the suffixing conventions is not primarily about improving spelling accuracy, it is about being able to analyze hypotheses about connections between words. We can test the hypothesis that "imagine" has a base "image" only if we know vowel suffixes replace final, non-syllabic "e" (image/ + ine —> imagine).

- The “structure and meaning test”: To determine that two words share a base, we need evidence from both structure (word sum) and meaning (etymology). So with the earlier example of words related to "play" (play, playing, playful, replay, playhouse), we can prove all of those words can be analyzed with word sums with coherent affixes and bases. But we can also show that they all go back to an Old English root plegan, plegian for “frolic, move rapidly”. However, the word "display" which can be analyzed structurally turns out not to be related. It does not belong in the morphological family with the others because it goes back to a Latin root plic(ere) for “fold”. So to “display” is to “unfold”.

“If we are going to teach children how their writing system works, we need to teach them the interrelation of morphology, phonology, and etymology. As we have pointed out, this is why Structured Word Inquiry (SWI) is not about “adding” morphological instruction to phonics instruction — its about teaching how the system works. This is why I argue that SWI teaches grapheme-phoneme correspondences more explicitly and accurately than phonics. Phonics instruction (under the definition of associations of pronunciations and letters without reference to morphology or etymology) cannot explain the grapheme-phoneme correspondences in countless words like does or rough or every or homophones, and so on. So many people miss the absolute detail into orthographic phonology that comes with SWI.

“Here are some videos to illustrate my point:

- Gr. 2 teacher showing investigations from his class Grade 2 morphology video

- Investigating grapheme-phoneme correspondences in a Gr. 1 class — with the context of morphological word sums Grade 1 morphology video

- A kindergarten lesson I taught introducing the word sum and matrix that touches on grapheme-phoneme correspondences like the pronunciation of the <-s> suffix for /z/ and /s/ Kindergarten morphology video

“It’s as simple as starting with the “known” and then expanding from that. Even if kids know all the words in a morphological family (e.g. play, playing, playful, replay, playhouse) the lesson is not about new vocabulary, but learning how word structure links words. That concept can then be applied anywhere.

“The other thing I keep in mind when choosing morphological families to investigate is the orthographic concepts a family has to offer. If I’ve established the fact that words that share a base share a spelling and a meaning connection, then I can introduce a base like with words like actor, acting, react, and action as a way to introduce the fact that the pronunciation of morpheme might change but keep the spelling. In that way we learn the phonology of t is not the “t sound”, but that the grapheme can write /t/ when that is the appropriate sound. I’ve attached an example of a lesson I’ve used for that before.

“I also draw on the <-ed> suffix from early on to highlight this same concept that morphemes do not have pronunciations until they are in a word. The pronunciation of a word like is another useful one to get rid of this idea of a “t sound” since this very common pronunciation of a very common suffix is what is typically thought of the “t sound,” but their ain’t no /t/!

“And then you also encounter words that give rise to the need to teach all the suffixing changes.

“These are concepts teachers need to learn and they can bring into work with their class as they investigate words.”

Shanahan again:

I don’t disagree with Peter on any of this, except I’m not as dismissive of the kind of list that you are requesting. I don’t see it as mutually exclusive from the curriculum goals that he specified or contradictory of the kind of instruction he described.

Many teachers, when referring to morphology or “structural analysis”, actually are talking about affixes alone, and not the bases. If that is the case here, there are some lists like that which present the most common prefixes and suffixes from textbooks in grades 3-9 (White, Sowell, & Yanagihara, 1989). You can easily find those lists on line and you could definitely make use of those lists to make sure that you are hitting all the notes if you do the word sums and matrixes that Peter recommends.

Otherwise, I haven’t been able to come up with a graded list of bases for you to use. But I have passed your letter along to my friends at MetaMetrics (the Lexile people) and have asked if they could produce such a list from their language corpus of more than 1 billion words. Stay tuned!

Tim, would you be surprised if research started to show morphology as a more effective early reading instruction than phonics?

Or, to say it another way, do you think there is a fatal flaw to the morphology over phonics as early reading instruction?

Or to the idea that early instruction should be phonemic awareness/phonics/morphology?

Thank you so much, Peter, for writing this and, Tim, for posting it. Ever since our initial lengthy discussion about morphology a year ago, I have become a better teacher by paying attention to and incorporating morphology instruction at all "teachability" moments in addition to planned instruction.

We certainly don't want to revisit the morphology vs. phonics debate (I think we have said it all for now and must simply await further research), but I just want to state the reason why I don't think the following statement is relevant to beginning reading instruction. Peter writes:

"Phonics instruction (under the definition of associations of pronunciations and letters without reference to morphology or etymology) cannot explain the grapheme-phoneme correspondences in countless words like does or rough or every or homophones, and so on. So many people miss the absolute detail into orthographic phonology that comes with SWI."

I just don't see the necessity of making these explanations to beginning readers, and after watching the kindergarten video posted--and previously the pre-school video on "rain"--I'm curious to see any examples of teaching non-readers how to blend and segment sounds in reading and writing (/e/ /gg/, /ch/ /i/ /ck/, /w/ /ai/ /t/, /w/ /a/ /tch/, etc.) with this stated emphasis on morphology. If there are links to teaching non-readers how to blend and segment that de-emphasizes phonics (grapheme-phoneme connections), I would love to see them. Once again, I don't want to re-open the debate. I'm just wondering what this beginning insruction actually looks like so I can see how it differs from my own.

Once again, I am so grateful that you have included this piece on morphology, and I will definitely continue to emphasize morphological instruction.

Thank you!

Many thanks to Tim for sharing this correspondence. I really appreciate the sharing of ideas whether we are always on the same page or not.

Hello to Robert and Harriett and thank you both for your comments.

I suspect I will have more to say later, but before the comment strings grow, I want to make a key point as clearly as possible regarding what you have both written.

Harriett raises the idea of a "morphology vs. phonics debate".

Robert asks about what the research might say about "morphology as a more effective early reading instruction than phonics."

I want it to be clear to all readers that I have never made any argument in the research or in any other context in which I am talking about "morphology vs. phonics."

My meta-analysis on morphological instruction (Bowers, Kirby & Deacon, 2010) looked at the effect of INCLUDING morphological content in literacy instruction across the grades and with able and less able students.

That is NOT about comparing morphology instruction to phonics instruction.

Instruction that could be characterized as structured word inquiry (Kirby & Bowers, 2010) grows from the basic premise that instruction should accurately reflect the nature of the domain being taught. In the context of literacy, that means literacy instruction should accurately reflect how the writing system works. Our writing system is a complex system that reflects the interrelation morphology, etymology and phonology.

I have NEVER promoted "morphological instruction" in contrast to "phonics instruction" or the other way around..

It turns out that understanding orthographic phonology in English means understanding the conventions that govern grapheme-phoneme correspondences. Not only does this mean learning what graphemes are available to write which phonemes -- it also means learning how the choice of grapheme is constrained by morphological and etymological considerations.

I reject both sides of this proposed "morphology vs. phonics" debate, because neither can represent how our writing system works.

In every piece of writing I've done on the subject in research, in comments on this blog and in my own practice I have always emphasized the idea that instruction of the written word should reflects the interrelation of morphology, etymology and phonology.

Those arguments should never be interpreted as even being relevant to any debate about "morphology vs phonics instruction". I'm not participating in that debate.

Harriett, with reference to my recommendations for bringing attention to morphological and etymological constraints on grapheme-phoneme correspondences in early literacy instruction, you write, "I just don't see the necessity of making these explanations to beginning readers".

There is another way of looking at this question.

I can argue, "I just don't see the necessity of AVOIDING the understanding of grapheme-phoneme correspondences that can be brought by teaching the meaning-structure clues inherent in our language."

I understand why my writing about this can be hard to understand.

It is so much easier for me to see what this instruction looks like and how children respond to it. In my work, I regularly see the clarity of understanding for grapheme-phoneme correspondences children gain who have struggled for so long in the context of isolated phonics instruction. Children who misspell the word "does" as *"dose" or *"duz" are excited to UNDERSTAND that this spelling is built on the base "do" and the suffix "-es". They are being given an understanding, not being told to memorize another irregular word. They are relieved to understand that their misspelling *"acshun" can't make sense because that doesn't have the spelling of the meaningfully related base "act". They can understand that the "t" grapheme of "action" links it to the spelling of the base "act". Suddenly something that seemed random and weird makes sense. And now they have the beginning of an understanding not only of these specific spellings, but principles that drive the entire spelling system.

What could motivate a young child learning to read and write, or a student who has long struggled more than gaining the sense that this writing system they are trying to study actually is actually UNDERSTANDABLE?

My own view is that anyone who is committed to instruction that helps children learn the "letter-sound correspondences" as effectively as possible should love structured word inquiry. It provides explicit instruction not only into grapheme-phoneme correspondences in words, but how to understand how and why they work for that word and its relatives in a meaningful context.

This view finds support in the evidence from meta-analyses and reviews about the effects of INCLUDING morphological instruction (again not morphology vs. phonics). That research showed that the greatest benefits were found for less able and younger readers. This finding is in direct opposition to what would be predicted by what can be described as the "phonics first hypothesis".

The findings from these meta-analyses and reviews support the hypothesis that we should include morphology from the start and that this is also particularly important for the less able.

I have seen zero research showing any benefit of AVOIDING morphological instruction with young readers or anyone else. In terms of the research I would add that the two meta-analyses of including morphological instruction by Goodwin & Awn (2010, 2013) the outcome that had the greatest effect sizes from studies which included morphological instruction was phonological awareness (d = .49 and d=.48 respectively). In both studies (the first for students with literacy difficulties, the second with all students) the effect on morphological knowledge (d= 40 and d.44 respectively) was second after phonological awareness.

I don't understand how these research findings are reconciled with the argument that morphology instruction should be avoided until after isolated phonics instruction.

I know you were trying to avoid re-opening the "debate" but your post and Roberts highlight that we seem not to be having the same debate. I'm hoping this adds some clarity to what I have been trying to put forward.

Thanks, Pete. I don't think this reopens the debate because these points have been so extensively articulated already (including your rebuttal to Ending the Reading Wars) that I really do feel we must await better research regarding how morphology fits in to approaching students who have no phonemic awareness and no letter-sound knowledge--i.e., beginning readers. Once these students gain the ability to "crack the code" with monosyllabic words, then everything you say about adding the morphological piece makes perfect sense to me. If you have any videos of what teaching non-readers to blend and segment on their own looks like with the methods you advocate, I would love to see these. The videos I've seen either involve students who can already decode mono-syllabic words or who are being taught morphemes--in, for example, eggs, watched, raining--rather than how to decode the words egg, watch, rain, etc. in the first place. Thanks for taking out so much time. As I keep saying, I've learned a lot, and your overall recommendations have made me a better teacher.

What Are your thoughts?

Leave me a comment and I would like to have a discussion with you!

Copyright © 2025 Shanahan on Literacy. All rights reserved. Web Development by Dog and Rooster, Inc.

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.