Teacher question:

What does research say about early literacy and when to begin? I am aware that kids may reach the stage of development where they're ready for reading at different times. What does the research say about the "window" for when a kid can learn to read? What are the consequences if they haven't started reading past that time?

Shanahan response:

Oh, fun. The kind of question that generates strong scholarly (sounding) opinion, with no real data to go on.

The advocates on both sides will bloviate about windows of opportunity, developmentally-appropriate practice, potential harms of early or later starts, and how kids in Finland are doing.

Despite the impressive citations that show up in the Washington Post, Huffington Post, or in various blogs, the truth is that there is no definitive research on this issue.

The meager handful of supposedly direct comparisons between starting earlier versus later are so ham-handed that I’m surprised they were even published.

One example is a longitudinal study that followed kids for six years… after either a dose of academically- or play-focused preschool. The research claimed that the kids taught early ended up with lower later achievement (https://ecrp.illinois.edu/v4n1/marcon.html).

That sounds horrible, until you look closely at the analysis and it becomes evident that the comparisons were questionable and the statistics specious (https://ecrp.illinois.edu/v5n1/lonigan.html). More of the play-group kids were retained along the way, so the final comparison—the one that finally found the difference the researcher was seeking—wasn’t between the same samples as at the beginning. The researcher’s response to this criticism suggests that the samples weren’t actually equivalent at the start either, further highlighting that this study couldn’t possibly reveal whether early teaching was helpful, hurtful, or not an issue at all.

I can provide examples going in the other direction, too. Since graduate school I have been told that young children are especially able learners and that the earlier we start teaching the better the odds that we’ll catch kids during that “portal of receptivity” (https://www.huffpost.com/entry/windows-of-opportunity-part-1_b_57c937cee4b06c750dd984b1).

The evidence behind that argument seems mainly to be based on the fact that from about 18 months to 5-years-of-age children learn an amazing amount of vocabulary; and that so-called vocabulary spurt is a real one. However, the idea that everything or even everything involving language is learned easily during those years is where the leap of faith comes in.

Reading development certainly does depend upon vocabulary, but there is much more to learning reading, and there is no convincing evidence that four-year-olds will learn to read more quickly or easily than would be the case a year or three later. Just because youngsters learn spoken words really fast, doesn’t mean that they are able to perceive the sounds within words (phonological awareness), or that they'll be able to master the names and sounds of the letters (the beginnings of decoding) especially easily.

When I argue for teaching reading to young children, my claim is not that we need to take advantage of a particularly beneficial time period when kids are most attuned to learning. (Though when I put forth such advice, I usually hear from those who, based on Finland’s educational attainment, claim that starting at 7-years-old is the magic ingredient to literacy success… an argument that neglects a few other differences between Finland and the English-speaking world, including homogeneity of population, relatively high economic advantage, formidable linguistic differences, and the fact that, according to the Finnish government, most of their children learn to read prior to entering school at age 7).

English reading can be challenging so I encourage as early a start as possible (and, no, research reveals no harm in this).

Starting early increases the amount of time available for kids to learn. Often kids enter kindergarten or first-grade with the expectation that they are to learn to read that year. Spreading this expectation across 3-4 years can reduce pressure and anxiety.

This also means that it is possible to successfully teach older students to read. We often hear the statistics that show that early reading problems persist. But these problems don’t persist because we missed some magical window of learning opportunity, but because we are not doing the things that will allow older students to succeed.

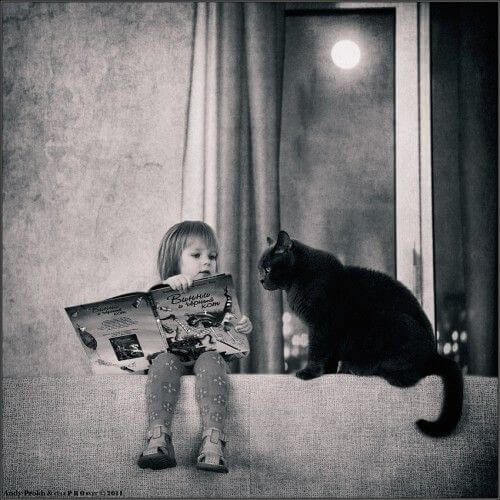

My advice, if you are a parent or caregiver, start introducing your children to literacy once they are born—reading to them, talking to them, singing to them, showing them how to write their names, writing down their stories, teaching the alphabet and letter sounds, playing with language sounds (e.g., “K-K-K-Katie”), and so on.

Of course, young children have brief attention spans. But that’s one of the benefits of starting so early—you can take advantage of 20 seconds here, 3 minutes there, over a long period which can make a big learning difference.

If you are a preschool, kindergarten, or first-grade teacher, begin teaching reading once you meet the children…

Give kids as long a timeline as possible and don’t worry about an optimum time to teach reading. There isn’t one.

The reason for starting early isn’t to capture some magic window of neuronal plasticity, but to make the window as big as possible. If teaching early identifies a youngster who struggles to learn reading, then we will have more years to address this youngster’s needs. The later we wait, the smaller that window of opportunity. We want kids to have the maximum opportunity to learn.

We hear a lot about “developmental appropriateness” these days, and this concept is used to dismiss the early teaching of reading—"don't teach reading until it is developmentally appropriate."

If that is what you are hearing I suggest reading the National Association of Educators of Young Children’s draft policy on this matter: “From infancy through age 8, proactively building children’s conceptual and factual knowledge, including academic vocabulary, is essential because knowledge is the primary driver of comprehension. The more children (and adults) know, the better their listening comprehension and, later, reading comprehension. Therefore, by building knowledge of the world in early childhood, educators are laying the foundation that is critical for all future learning (How People Learn I and II). The idea that young children are not ready for academic subject matter is a misunderstanding of DAP; particularly in grades 1-3, almost all subject matter can be taught in ways that are meaningful and engaging for each child (citations).”

Developmental appropriateness has more to do with how we might teach something successfully than with what we teach. Keeping lessons brief and lively makes great sense with young children (and it doesn’t hurt the older ones either). Teaching phonemic awareness with songs and chants is a great idea, and it can be fun to play games built around letters and sounds. Introducing reading and writing through play areas set up like post offices, restaurants, libraries, and the like are all developmentally appropriate for the youngest of our preschoolers.

Start teaching reading from the time you have kids available to teach, and pay attention to how they respond to this instruction—both in terms of how well they are learning what you are teaching, and how happy and invested they seem to be. If you haven't started yet, don't feel guilty, just get going.

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.