Teacher question:

I’m confused. I’ve worked with Lexiles for years and my district provided us with a chart showing the levels of books to use for each grade level. Then Common Core came along with a different chart that put different book levels with each grade level. I don’t live in a Common Core state, but I’m still not sure which chart to use. Can you help me?

Shanahan response:

It’s funny, but no one has ever asked me that before.

What makes it funny is that you’re not alone. Most educators have no idea of the reason for those two charts.

Let’s start with the basics.

Lexiles is a readability measure. Readability measures are mathematical formulas that transform the structural properties of texts into predictions of how well readers will comprehend those texts.

For example, Lexiles counts the number of uncommon words and the average sentence lengths in a text and then uses that information to guess the likelihood that average readers will be able to understand that text.

Of course, there is a lot more that goes into making a text difficult than the words and sentences, but that information alone is enough to allow for a reasonably accurate guess about comprehensibility.

The reason Lexiles or any other readability estimate can do this with so little information is because most authors are pretty consistent in how the features of their texts work together. If the vocabulary and syntax of a text are appropriate for a sixth grader, don’t be surprised if the same is true for the organization, content, cohesion, use of metaphor, and so on for that same text.

Of course, there authors who are noted for their inconsistency. Hemingway’s syntax, for instance, appears to be pretty easy in readability predictions. But readers usually find the interiority of his presentation, the subtlety of the actions, and the cohesion demands of his texts to belie the Anglo-Saxon vocabulary and nubby little sentences. That means readability measures of Hemingway are likely to underestimate the actual challenge of making sense of his books. (That’s why middle-schoolers struggle with The Old Man and the Sea despite the rosy predictions for its comprehensibility.)

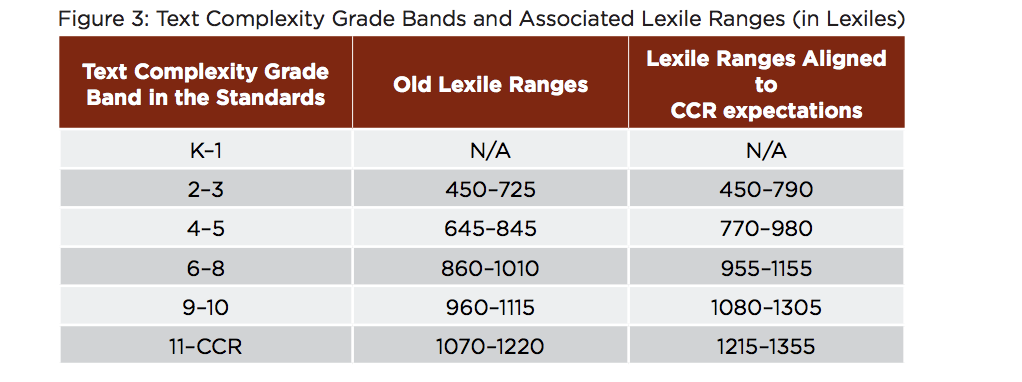

Here is the Lexiles chart that you refer to. In the middle column it shows the predictions of how well students are likely to comprehend a text. If a text is at 700L according to that chart, that would mean that Lexiles is predicting that an average fourth grader would read that text with 75-90% comprehension (and it predicts that because that’s how it has worked with thousands of fourth graders with such texts in the past).

That may be an old prediction, but it is still the right prediction if it is comprehension that you want to predict.

The Lexile ranges aligned to Common Core are another thing altogether. Those numbers don’t tell us how well students can read particular texts. These are aspirational levels. They indicate how hard the books need to be if students are to be on track for graduating high school with sufficiently high reading levels. Those levels are not predictions of how well students will read a book, but a statement of how hard the books need to be if kids are to succeed.

I think a lot of teachers misunderstand this. They think that readability estimates and Fountas & Pinnell levels, etc. tell about “learnability.” They think if they match students to the right books, then the students will make optimum learning progress (and placing them in easier or harder books will interfere with this progress).

However, it’s kind of the opposite. Readability estimates predict comprehension, not learning. Lexile scales and book leveling systems provide gradients from easier to harder in terms of how well the texts are likely to be understood. But if students can already read texts with 75-90% comprehension without teacher assistance, then “teaching” kids to read from those books should be a non-starter. Instead of stretching students to handle harder texts (the Common Core column), they are focusing on having kids practice with levels of demand they have already conquered.

You didn’t ask about it, but another important confusion is between readability and suitability.

To sort this one out it may be useful to think of texts as having two levels of complexity. One focuses on the linguistic demands of the presentation (the one measured by Lexiles and other readability measures), and the other on the appropriateness of the content and of its depth for the students.

Take The Great Gatsby, for instance. The linguistic demands dimension emphasizes the likelihood students will gain the declarative meaning of the text. Lexiles predict that a sixth grader should be able to “comprehend” this text, and it wouldn’t surprise me at all if such students could read it and recall important information from the book, such as Nick’s neighbor was Gatsby; Nick’s cousin was Daisy; Daisy was married to Tom; Tom was having an affair.

The second aspect of complexity focuses on the sophistication and appropriateness of the content, not the linguistic presentation. Perhaps sixth graders could read this book and provide the kind of answers noted above, but do I really want them, at age 11, reading about Tom’s sexual affair? And, Gatsby is a book with a lot of levels of meaning. Would an 11-year-old be able to profitably get the facts noted, while simultaneously gaining purchase on the symbolism (e.g., the green light, the closing of the window, etc.)

That middle school students could read Gatsby with reasonable levels of comprehension does not make it suitable – in terms of content or the multiplicity of interpretation of which the book is capable. A sixth grader could read it, but I’d not require it until 9th or 10th grade. It is simply more sophisticated than the language it depends upon.

American English teachers have become expert at identifying books like Gatsby; that is books that a large percentage of students can comprehend easily because of the limited language demands of these books. In other words, they select relatively easy to read books that are suitable in terms of the content and sophistication of ideas.

Common Core has pushed teachers to assign texts that are not only suitable, but that have enough linguistic complexity that they will enable students to negotiate more difficult texts.

There is certainly nothing wrong with assigning a book like Gatsby in ninth grade, in spite of its relatively easy language, as long as students are also learning how to make sense of other texts with greater linguistic demands.

Unfortunately, this information is not well or widely understood by teachers.

As text levels have inched up due to more rigorous standards requirements, teachers have been chagrined to find students struggling to make sense of grade level texts, when previously they could have read these with relative ease.

According to surveys by RAND and Fordham, as the books selected for teaching have gotten linguistically more difficult, teachers have been less inclined to teach with grade level books. Instead of teaching the students to make sense of the more complex language, they’ve avoided the problem altogether by going with easier texts.

Remember those language levels established in the standards show how hard the books need to be in terms of linguistic demands if the students are to succeed. Falling back to the “old Lexile” levels will certainly ensure that kids can understand the books that we are using, but they won’t give students the opportunity to learn to deal with the sufficiently texts that would prepare them for success.

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.