Blast from the Past: This entry was first published on December 13, 2007, and was reposted on March 15, 2018. Recently, the publishing industry revealed a big plunge in e-book sales accompanied by steady gains in the sales of traditional books. Much has changed since 2007 when this blog entry was first posted: tablets and larger phones have caught on, batteries have improved, more books are available in digital form and they are easier to buy and access--and, yet, the book hangs in there. I now regularly read both ebooks and paper ones myself, but ebooks are not likely to replace the paper ones until we--through advances in technology or teaching--improve readers' abilities to comprehend and remember the information we gain from electronic books. We simply don't read them as well as we read paper books.

I’m amazed at the persistence of the book in spite of dramatic advances in information technology over the past fifty years. The book—a 1500-year-old invention—not only survives, but thrives. The computer revolution has changed how we buy books (thanks, Amazon), but the fact is we still buy books, rather than disks, tapes, MP3 downloads or whatever this flavor-of-the-month’s info format may be.

Tech companies hope to lure readers away from paper-paged books in favor of their sleek electronic readers (reminiscent of the old Marlene Dietrich films in which she’d try to steal the hardworking men from their loving wives). I’m sure the manufacturer has great hopes—and the newest e-book is admittedly better than past attempts to replace pages with bytes—better because this one looks like a book (imagine Dietrich without the mascara). Maybe this electronic hardware will persuade us to jilt the book, but I doubt it.

Why do books persist? Part of the draw is that the book is a highly evolved technology. Books fit into a complex functional niche particularly well, making them especially hard to displace. One aspect of this functionality is portability. There are coffee-table books that may weigh several pounds, but most books are small and light: small enough to allow a woman to slip the latest Barbara Kingsolver into her purse or for a soldier to carry a Bible in his camouflaged blouse on an Iraqi battlefield. While I can read a book on my PDA, Blackberries make for poor reading experiences, because of glaring screens, small print, and short lines.

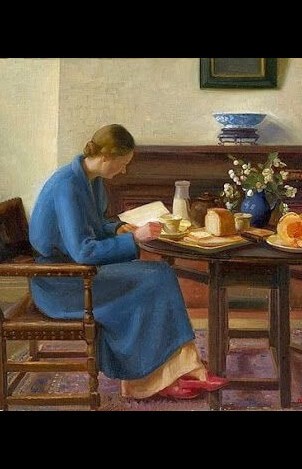

Books are also remarkably versatile; they fit well into the nooks and crannies of our lives. I can comfortably read a book on the beach, in bed, or on an airplane. Books are ready to go when we are; there is no waiting for them to boot. On long trips, I worry about computer batteries, but in books I trust.

Reading any kind of book—paper or electronic—is rewarding because of the author’s ideas and language. But books offer additional aesthetic pleasures. Book reading is not just a visual experience, it is a tactile one. We describe exciting reads as “page turners” and talk about “closing the book” for a reason.

Many years ago, I was reading Charlotte’s Web to my daughter. We scrunched into an over-stuffed armchair, the only sound, the sound of my voice speaking E.B. White’s spare diction. Erin sat in my lap in her fleece nightgown, and I held the book in both hands, encircling her warmth in my arms. I can still feel the flannel against my arms, the heft of the book, and the soft textured paper under my fingers. When I read of Charlotte’s death, Erin burst into tears. Someday fathers may read e-books to their children in the same way; but, of course, it won’t be in the same way.

Comments

See what others have to say about this topic.